The Williamson County Juvenile Justice Center recently implemented a new and groundbreaking program that, according to District Judge Stacey Mathews, is already being looked to for duplication state-wide.

“Being at the forefront of juvenile rehabilitation and care is nothing new for Williamson County and this is the part of my job as Judge that makes me most proud. This program is so beneficial for the kids and will certainly find support from the community.”

The concept for the “Core” program was developed by Assistant Chief and Director of Mental Health Services Matt Smith. Judge Mathews, who has been the Juvenile Judge since November 2015, was instrumental in its approval and initiation. Executive Director Scott Matthew is responsible for implementation of all Center programs and therapy, and is well-known and respected state-wide for compassionate and effective rehabilitation.

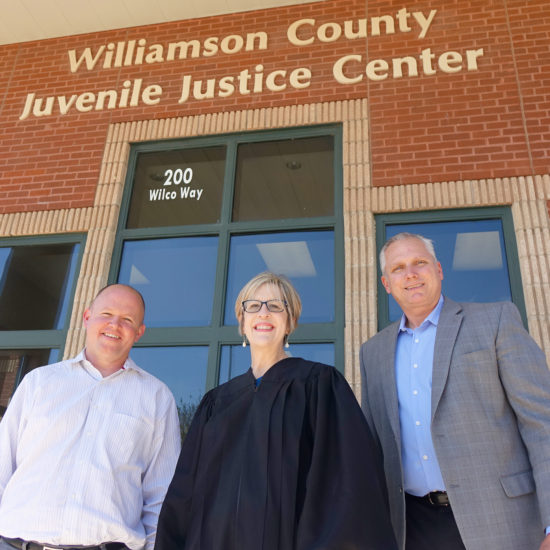

Prime movers of the Core Program, Assistant Chief Matt Smith, Judge Stacey Mathews, and Executive Director Scott Matthew

The Core Program

The Center previously managed three residential programs with different philosophies and security levels under the same roof.

Core absorbed all three into one secure program that takes a holistic approach to the kids’ care by identifying and addressing what possible trauma or abuse may have led them to be in the justice system in the first place.

The program breaks down existing services to an individual level and provides customized therapy and rehabilitation. Just a few weeks in, they are already seeing results. Smith says, “We are expanding on a program from the TCU Institute of Child Development. They use an evidence-based framework for how to intervene with kids who have experienced trauma.

“Our Core program is based on Trust-Based Relational Intervention (TBRI) and it is all about looking beneath the surface of our kids’ behavior or their offense and find out what their true need is.”

Smith began working on the concept several years ago with Triad, a secured unit program that went alongside the non-secure Academy program, begun in 1992. “It was time to morph them all into one secure program in an effort to keep kids closer to home. In the past if we had kids who didn’t perform well in our program, we didn’t have a space for them and had to transfer them to another facility. Now we have the services and the appropriate space to keep them all here in Williamson County. “

Executive Director Scott Matthew agrees, “Much of the research comes out of the foster care system because all of these kids share similar backgrounds of neglect, abuse and trauma. Now, instead of the boot camp approach, we are looking at the whole child to find out what needs we can address. Treating the root causes related to trauma rather than just the symptoms and behavior results in more long-term, internally-driven positive change.”

A “Cafeteria” Plan

All of the kids in the Center will continue to receive standard care; counseling, education and physical activity, but the Core program breaks down services to the individual level. Much like public schools create Individual Education Plans (IEPs) for every student, the Center will do the same based not only on offenses, but also the background and circumstances that led to detention.

The Center boasts a robust treatment team that works with the kids. In addition to direct care providers—counselors, officers, etc.—who are with them all day, each has a case manager to assess, develop and tweak program initiatives during recovery.

“All of us have the same goal,” Matthew says, “to never see these kids again. The intent of these custom services is to shorten the length of stay for each kid and to reduce or remove the chance of recidivism.”

Safety & Security

Previously, varying levels of security required that when a resident got in trouble and had to be removed to a more secure environment, it meant a trip back to see the Judge. Now, the Core program is under one roof with a single level of security. As well, the perks kids receive as they graduate through each level toward release are fluid. “We control the processes better and it’s less additional stress for the kids,” Smith says.

“It’s easier and more efficient for everyone to be able to remove a privilege than to have to go through the process of seeing the Judge again. If a kid doesn’t want to participate in an activity, or gets into a fight, we don’t have to have any lockdowns. He or she can just stay in a private room because it is all secure; we don’t have to go back to the Judge or make any substantial changes to his or her program. We can keep everyone safe but continue to move forward to going home.”

While the Center has removed the “boot camp” aspects of detention, they are maintaining the ROTC program for those kids who can benefit from the structure and discipline.

Smith says, “Some kids thrive in a military structure while others crumble; we don’t want to put everyone into the same mold. They still have all the problems they did before, but we can use a Montessori approach to putting them in a plan where they will flourish and recover; they simply get whatever it is that they need.

“For some kids, addiction is what led them to be here so we provide drug counseling. For others it might be a sexual offense, so in addition to school, they will receive specialized therapy for that. Or maybe they need both, and now we don’t have to relegate them to any particular track at one time. We can provide either or both.”

In the new program, kids work through “leveling” toward release and they receive custom services via case management. They also earn privileges along the way. “Everyone gets school,” Matthew says. “Some kids are here for very serious things and rehab is critical but they also still have to earn simple things like wearing jeans instead of a uniform. Once they accomplish certain things they can earn a furlough for a day or a weekend. If someone is having a hard time adjusting or leveling up, we can move him or her into a more or less structured environment and re-evaluate the services depending on that person’s IEP.”

Matthew says they will also continue with their many therapeutic activities; art, culinary arts, sports, music, construction and more. They are always open to community members who have skills to share. “Anyone is welcome to work with our kids, whether it’s basic auto maintenance or photography, we try everything we can in hopes we will stumble upon the one thing that will light that spark and turn a kid around.”

Community and Commitment

Judge Mathews is the program’s biggest advocate outside the Center. “This is what I fought for as a teacher and it is why I went to law school; to meet kids where they are, focus on their strengths and address their needs. Caring for children carries over from home through a classroom and into the justice system.”

The Judge recalled the case of a girl in the system who had been trafficked at a very young age. “She was so damaged and came from a home where drug abuse was normal. I want to think that we have the right tools to take care of her here when, in other places, she might just be thrown away.”

Smith agrees, “With the intervention training we are providing to our staff, they are even more committed and invested in positive outcomes for these kids. We’re doing more than just removing these kids from society and hoping they won’t be a threat again. We are making lasting change to create successful adults with job and independent living skills.”

Special Advocates

Another new aspect of Core is that each person will have an advocate attorney. Attorneys will guide kids through the system, be on their side and make sure they don’t get “stuck.”

“Having attorney advocates is unique to us across the nation right now. When kids arrive here and suddenly there are a half-dozen grownups managing everything they do, even in their best interests, they can sometimes feel like they are being ganged up on. Attorneys will be intentionally and professionally on their side so it is our hope kids, and their parents, will have more hope and trust throughout the process,” Matthew says. “The attorneys will be physically here as well rather than having the kids travel to and from court so it saves time and tax dollars too.”

They are applying for a grant from the Indigent Defense Commission to fund the fees for the attorneys as a judicial best practice.

The Numbers

The Juvenile Justice Center will maintain the same number of beds, 55 for males and females. Each person arrives in a secure setting with individual rooms and secure activity pods. They then progress through the program, achieving less and less security and more incentives as part of a phased reintegration back home.

Each resident will be assessed up front to determine which services will be most effective in breaking down and recovering from past trauma or abuse.

“It’s a work in progress,” Smith says, “and we know we will make changes along the way. Right now each person stays an average of six to seven months and we hope to reduce that. It will take about six months to cycle through a good number of kids and look at the outcomes but right now it is working. Meanwhile we are watching the state legislature for changes to the laws regarding age of criminal responsibility, which will allow us to make changes again in our casework.”

Director Matthew says, “Basically we want to give kids hope for a better future through programming. I am committed to and care about these kids but for people who are not in a position to see behind the walls, I always say that with kids you can pay now or pay later. We are always much better off providing education now than incarceration later. Spending a dollar today to teach ethical behavior and how to be good parents will save two dollars when that person grows up to contribute and give back rather than being any kind of drain on the system. The implications of doing it right, now, are always our most desirable outcome.”